Broadening the Arc of Devotion

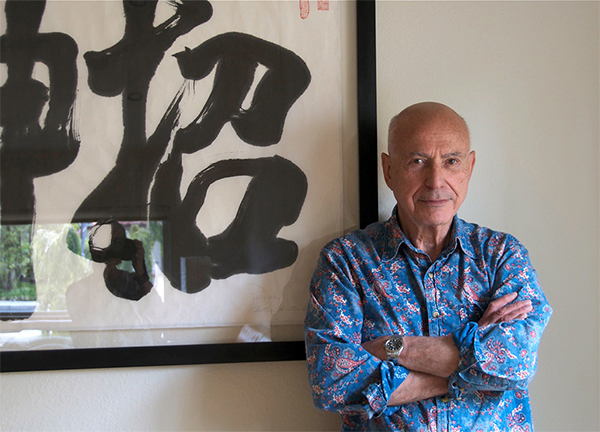

Alan Arkin 2012 © Suzanne Arkin

A Conversation with Alan Arkin

Alan Arkin has been a major star of stage, screen, and television for nearly fifty years. Best known for his roles in such films as Wait Until Dark, Catch-22, Edward Scissorhands, and Little Miss Sunshine (an Oscar-winning role), Arkin is also a master teacher. Along with his ongoing work as an actor/director/writer, he has taught retreats at The Omega Institute, Bennington College, and Columbia College. He is the author of An Improvised Life: A Memoir, and for almost half a century he has been a student of Vedanta and Kashmir Shaivism.

This previously unpublished interview with Alan Arkin and his wife, Suzanne, about their improvisation workshops took place over brunch at a busy diner and at the Arkin home in Santa Fe in June 2005.

--David Ulrich

David Ulrich: Philosopher Jacob Needleman articulates the question: “We obviously cannot confront this tangled world alone. It takes no great insight to realize that we have no choice but to think together, ponder together in groups and communities. The question is: how to come together and think and hear each other in order to touch or be touched by the intelligence we need.” How can groups of people “share their perceptions and attention, and through that sharing become a conduit for the appearance of a spiritual intelligence?”

Alan, I know in your work with improvisation there seem to be many different dimensions of people coming together, making mutual discoveries, and having one’s work with each other spark ones’ own discoveries. How does that take place?

Alan Arkin: Something happens in the workshops that is transforming for people. It’s what I had hoped for, but it’s happening in a broader way then I ever envisioned. It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I realized why I don’t want to teach acting and why doing the improvisational workshops is so exciting. If I taught acting for fifty years, I’d be lucky if out of the hundreds of people I worked with, two or three people would learn how to fly, to get out of their own way. But at the end of a two-day improvisational workshop, we have, out of a group of twenty, eighteen or nineteen people that are soaring and it’s miraculous.

DU: How do they come to that ability to soar?

AA: It’s a combination of things that I am only a part of. This is not my own design, but the feedback we are getting from a lot of people says that Suzanne and I bring to the workshop a completely accepting attitude, that we don’t have the need for them to be good or bad or to get anything out of it. I think people respond to the fact that we don’t have a specific need except for them to have a good time.

DU: So you’re nurturing and creating an environment where people can come together, and in that coming together there is a power in the group dynamics that brings something to life.

AA: That seems to be what’s happening, The design of the workshop itself has people fly. If I have an agenda. it’s wanting to see people get out of their own way and have an experience where they’re going places that they didn’t know existed—to what athletes call the zone. But that is an individual experience. The sense of the group dynamic, which I think even takes precedence over the strictly individual experience, has become kind of awesome. By the end of a weekend, we have twenty people that are bonded for years.

There is nothing that we can say, no amount of words can describe the kind of atmosphere that gets set up in the workshops. It’s the atmosphere, which is a wordless matrix, that somehow is responsible for this event and I don’t know how it happens. Yet as I look back on the way the workshop was set up, the entire first third of it is a series of exercises that force people to depend on each other, so that a sense of interdependence is built into everything that comes afterwards.

DU: In what way does this take place?

AA: My first exercise is to get twenty people in a ring. They don’t know each other and they’re all terrified. I tell them the rules for this exercise: I don’t want to see anything interesting and I don’t want to see anything creative. And immediately twenty people’s shoulders go down and they breathe a sigh of relief. They say to themselves: "Well thank god I don’t have to do what I came here for. I don’t have to be the thing that I wanted this workshop to accomplish for me." Then what we do is just play imaginary ball for about ten minutes, and we keep changing the nature of the ball. The ball will become a bowl, it will become a piece of rope, it will become a small suitcase, and at the end of five or six minutes everybody’s laughing, having a good time, and being enormously creative. At the end of the exercise I ask: "What happened, what were the instructions for this?"

I tell them: "You failed! The instruction was not to be creative, not to be interesting." I then ask, "Why were you creative?" And every once in a while someone realizes the answer: that it’s our nature to be creative and that not being creative is the aberration. When we leave ourselves alone, when we’re flowing like we're supposed to flow, without getting in our way and censoring ourselves and trying to please our parents or some teacher or some idea of who we would like ourselves to be, we automatically go into a creative mode.

In this exercise it will sometimes happen that the energy goes out of the circle, particularly when people start slowing down and trying to be clever and entertain us. That’s why one of the other things I say is to keep it going, keep the object moving, no time to think—I don’t want to see thinking in this exercise.

In the second exercise you start with one person performing a motion, any kind of motion, and you tell them that these eight people in the group are going to be one machine. The first person begins a motion, the second person has to add on to that, the third person has to add on to that until the eight people become one cog and one piece of machinery.

SA: Initially they don’t touch each other. They don’t know each other very well and are a bit standoffish, so we encourage them to do it again and to touch each other this time, which starts to connect people.

AA: It gets instantly more interesting. The way I describe it is that when people are touching, something can happen. In this case the exercise is purely physical so it’s a physical touch, but it doesn’t have to be a physical touch—like in most of the other exercises you sense when people are connecting with each other, it is often a form of touching that doesn’t have to be physical. The next exercise is getting groups of three people together and giving them some common task that they have to solve together—like putting furniture into a room in a specific way. Of course there is no there’s no real furniture, it’s all in their heads.

DU: You’re guiding people away from trying too hard. Is there something about the group dynamics that helps each individual become more creative and interesting?

AA: Yes, sooner or later—it usually happens pretty soon into the experience—you’ll see somebody take a big risk, and once somebody takes a big risk I think that it starts dawning on other people, my god they took a big risk and nobody’s denouncing them or criticizing them.

DU: What is your own work within the group? You both seem to get into the thick of it; you are there attending to whether or not somebody is functioning from their ego and trying to pull them back to a sense of authenticity.

AA: Yes, I feel it’s the only real function I serve of any importance in the group. I tell people early on, that the only thing I do not want to see on this stage is any self-congratulatory, Saturday Night Live, smart-ass stuff. And I ask, how do I know when you are doing that, and when you’re not? I have an almost infallible guide that tells me when somebody’s being truthful or whether they are showing off—and that’s my rear end. If I find myself sitting forward in my seat, something is really happening and it’s interesting because it’s out of ego control. If it’s smart-ass stuff, then I find myself sitting back on the chair and saying, ooohh he’s clever, but he’s not engaging in the event. It’s a gauge that I have that I feel I’m good at because I pay attention to it. And it’s something everyone in the group can have access to. I tell them, just watch yourself and see where your attention is as you watch other scenes. And watch if your attention is pulling you back into the seat or whether it’s pulling you forward into the event.

DU: That’s a very important role because your being honest with your own responses, and by being honest you’re helping each individual become more authentic within themselves.

Inner work is infectious, is it not? If everybody is working in a way that attempts to get beyond their ego, and to both witness and challenge their implicit assumptions, something can come to life that is of a different quality. How can we get from a strictly group dynamic to accessing this larger wisdom that both lies within us and surrounds us?

SA: It’s about intense devotion.

AA: Yes, I think that’s the key. And it can be devotion to anything. The way that I talk about it is—one of the signs of being connected is being in the zone. That is a huge step, but I don’t know how you go between the normal state of walking around and what I call the zone, where things are flowing and effortless. In my experience with people who have been in that zone, it can occur in any walk of life, but it has to be accompanied by an intense devotion to whatever mode that zone appears in.

A lot of athletes can tell you that the zone is being in a place that’s timeless, a place where they can’t make mistakes, where everything slows down, where they know where every teammate is, where they know that they’re going to get the ball even though they haven’t yet been passed it. They just know things they have no way of knowing. They’re out of the way, they’re a vehicle rather than imposing themselves in any way. Your ability to reach the zone in different areas of your life depends on where you have placed your devotion. Without intense devotion, I don’t think it’s something you can ever touch on. I had this experience with acting for many years, but I made an interesting mistake. This was the most exalted place I had ever experienced, and I really thought that acting gave me that experience, that the god of acting brought that experience to me. What I didn’t realize until years later was that there is no god of acting, there is no special acting place, that my devotion to the craft of acting gave that experience to me.

DU: What. Oh no! There is no god of art?

[Laughter.]

AA: Well… who knows? But I do know that I brought my devotion to the craft of acting. The next step from that—and it’s another huge leap—is for people to realize, wow, if I experienced this extraordinary and exalted state in this little area, maybe if I extended my devotion, if I broadened the arc of my devotion, maybe I can experience it in other walks of life, in other places of my life.

DU: Broadening the arc of your devotion. That’s a beautiful concept.

When you broaden the scope of your devotion, does that energy extend to your workshops? Also, as the individuals in the workshop begin to broaden the devotion they bring to the task, does that help the other person they’re working with? What are the steps in the workshop to bring people to that place together?

SA: Some of them are very simple techniques, like intention. We ask the participants to not go into the playing area unless they have an intention. This basically means to have some kind of need and to drive that through the entire scene, not to ever let go of that intention unless the other person says something or has a strong enough intention to organically take you in another direction—which you need to do of course in improvisation.

I think that the concentration that intention brings can begin the process towards connection. With intention, concentration, and then somehow with that deeper level of concentration, I find myself sometimes in that zone.

I think it’s also by listening. By listening I mean when someone can really hear what’s being said, or what’s being transferred, I mean, not just in terms of words, but in terms of an energetic level as well. Actually listening to what’s being said, and feeling that you’re being listened to, is, for me, miraculous. How many times during the day do you really feel like someone’s hearing what you’re saying. It’s just so rare. I think that gets you into another realm—through attention.

DU: Could you say something about how we connect with these subtle energies through attention? The sculptor, Isamu Noguchi, talks about creativity as something that we access that he describes as “flowing very rapidly” through the air. Do you touch that in your improvisational workshops?

AA: It’s become very simple in the workshop. As far I’m concerned, every great performance—every great performance in the workshop, in the world, in movies and television, to me boils down to two things: intention and the emotion or feeling connected with the intention. Emotions and feelings are two different things, but I’ll get to that later.

Once we get past the first exercise, I say that I don’t want to see anybody get up on stage without an idea. I don’t want to see anyone just spew. I want to see people go on stage only when they have an intention of some kind. Once they have the idea down of not going on stage until they have an intention, they can rarely make a mistake. You will never have a boring scene, it will never be devoid of contact or connection of some kind. That’s on a very mundane level but it will work, it will always work. Once you have that idea down, then we work on the idea of filling that intention with something personal, something that’s emotionally, kinesthetically personal to you. Because if the intention stays intellectual, you’ll get into the place of being a playwright on stage and you’ll be pretending to relate to somebody while you are watching this typewriter going in your head.

One of the exercises I like to give is of simple buying and selling where the intention is built in. You come into the store, your intention is to buy something, the other person’s intention is to sell something—so the intention is mutually there. But your connection to the buying is what will turn it into an event rather than just a transaction. The depth of your connection with it, your emotional or feeling connection with it, takes it from being a transaction to the possibility for it being an event.

The minute you have a feeling connection with the intention, then you have a live organism up there.

DU: Your mutual participation in the workshop seems important. You seem to help each other and your connection with each other seems profound, in terms of helping to encourage a flow of energy. There’s a tone that comes through in your relationship. It sparks feeling and I’m sure that the student’s feel it also. Do you think that the energy that you two embody as partners touch the participants of the workshops on a level they might not even be aware of?

AA: It’s not something we do consciously, but we’ve gotten at least fifteen or twenty letters over the past few years acknowledging that. We don’t feel like it’s profound, we just know we love each other and try and stay open. We have our own perspective on what a relationship can be like and we don’t have any sense of doing anything.

SA: I know this sounds so romantic, but we have a deep connection, a very deep love for one another and I think people pick that up. And they also tell us that they feel loved in the workshop. They have said that to me often, and I feel that we do love them in this process, that we’re somehow nurturing.

DU: Is it an impersonal kind of love?

AA: I wouldn’t say it’s emotionally charged. But every once in a while it gets like that when somebody does work that’s incredibly deep and very revealing. It will engender some kind of a more personal light for a little while.

There’s a great statement that I heard on national public radio that made an enormous impression on me when they were interviewing a Greek orthodox monk. There was something about his voice and the way he was speaking that really captivated me. Finally there was a question to him that I thought was fascinating: “Do you find that you’ve changed, can you track the changes that have taken place in you in the twenty-five years that you’ve been a monk?” And he said: “Oh yes, I can. I feel enormously different from the person who I was when I started out. Twenty-five years ago I was a very passionate person. Now I don’t see myself as a highly charged emotional person anymore, but I think of myself as a person of much finer feeling, and that I’m a much more feeling person.” I said, god, what a great and fascinating distinction between a highly emotional person to a person with deeper feeling. I spent a lot of time thinking about that and I even looked into the roots of the word passionate.

Passionate is related to the idea of torment and suffering, and a genuinely feeling person is somebody who has their feelings accessible to them, which you don’t have when you’re in a state of passion. You may have one single feeling accessible to you but the panorama of them will not be accessible.

DU: Gertrude Stein once characterized American writers as having passions, but not true passion. I think she was making something of the same distinction. It seems to me that this quality of feeling, or this quality of love that you feel is what can bring us to a different quality of attention and a different quality of perceiving life. Is there something about this difference in passion and feeling where we tune ourselves, if you will, to a higher vibration? What is the role of feeling in opening to the wisdom that lies within us and surrounds us?

AA: I think it happens, I don’t think it’s something you decide. I think if you take care of the early stages, which is being attentive to your feeling states, then that’s kind of a natural byproduct of it.

SA: I think it’s also a form of grace. When we’re in the workshops, it’s not that I’m saying to myself, okay now I’m going to do this in order to get to that higher place. What happens is that somehow we’re able to open ourselves enough to be used in some way as an instrument of grace.

In terms of what someone may believe in, whether it’s a spirit or god or Buddha, perhaps when we find our way of helping or serving, we open at those moments to that force and have it flow through us to help heal or help teach or help change. I have to honestly say—and not out of any kind of humility—that it really never feels like I have anything to do with it. It feels as good for me and as healing for me as it feels for participants because of this thing that’s flowing. And sometimes it does feel like maybe I’m being used, but maybe they’re also being used to give it back to me.

AA: The point of entry for this experience was when I was a kid. The only way I knew anything then was through the filter of theater and film. I wanted badly to have that sense of flow and power—which I didn’t have at that time. But I would watch people and would find that there were some people that had a deeper intuition about things. I found that what was almost invariably true with these people, was that they had less agenda than others. They had a fluid ability within the structure of their lives to change, to go in different directions and that seemed to be a constant. This is the atmosphere I want to create with the workshop. I don’t have any need to be a mentor. If the workshop fails, I don’t care, if it goes well it’s wonderful. I do care but it is a different kind of caring. It’s impersonal.

I think that the need an artist has to manipulate the world indicates some kind of aberration. What do you need to manipulate it for, it’s fine the way it is. The work will do itself, the thing will do itself. There’s a level of trust here.

DU: I keep coming back to this question about trust, that we trust the creative process to proceed on its own, with our participation to be sure, but that we allow it to move in a certain direction. Does something else take over, do invisible energies contribute to that process? Do you find that there is a greater intelligence available?

AA: My god, it’s everything.

SA: Yes, and in the workshops you have to establish some form. So we start with throwing the ball in a circle, and then after a while the exercises almost disappear. Something else is happening. We’re doing it but something else does take over.

AA: Talking about invisible energy, it doesn’t take a genius or great mystic to know that if you’re connected deeply with somebody and you walk into the house and they’re in another room and they’re in a lousy mood you can feel it. I would say millions and millions of people experience that. Because when you walk in the house, you open yourself, you relax, and you have a close relationship with this person so you allow it. But most people don’t allow it in other places, they shut down, they shut down those impulses, they allow tensions to take over. But it’s something that everybody’s got. Whether you choose to make use of it or not is an individual thing.

And the opposite is true also. When something has an extraordinarily warm and loving atmosphere you can, you can pick up on that.

How do we broaden the arc of that devotion? One of the questions we’ve been getting more and more lately is terribly sad. People say at the end of the workshop, okay this is all very well and good but what do we do in the real world? This question makes me laugh. The workshops are very much the real world, but if someone feels a deeper sense of freedom and safety there, it becomes their responsibility to carry this with them and insist that it becomes part of the rest of their life—which is a pretty big order, I know. And not a lot of people are going to be able to do it right away.

DU: It gives people a taste of something. And then they do have to do the work in order to bring it into their lives. But it shows them it’s possible doesn’t it?

AA: My teacher, and a lot of Eastern thought, says that you don’t need to be taught anything. You need to remember, you need to shed skin after skin after skin until the truth, which is within you already, just starts revealing itself to you. With some help along the way, like prods—a mentor here or a mentor there.

I use the metaphor frequently in the workshop of learning how to use one’s voice, how to become a singer. I studied voice for a couple of years and my teacher drove me nuts because for a couple of years nothing he said made any sense to me. It ultimately came down to either yes or no. Then one day, after about a year and nine months, I sang from the right place and everything he said finally made sense. But up until that point he might as well been talking gibberish. The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon. You can talk and talk and talk, but until you have the experience of letting go, all you can do is believe that this guy doesn’t sound like he’s lying. Get out of the frontal lobe, get shoved down to the rest of your system. You have to have the experience of letting go in order for anything to really sing for you.

In the workshops, I’m happier being a wild man, I’m happier being God’s fool. I have to keep myself from saying outlandish things all the time to people or the opposite, saying them too rigidly. So I want to be God’s idiot and I’m working on that.

Interview first appeared in Parabola Magazine, Vol.37, No.2, Alone and Together