Longing for Light Overview

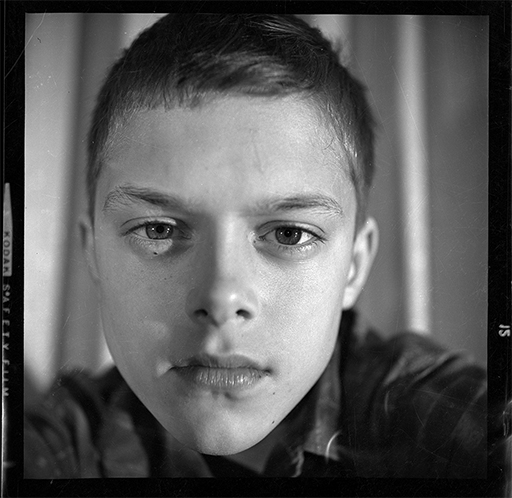

Self Portrait, David Ulrich 1962

The gift of observation, of the inner and outer worlds and their profound relationship, can be cultivated indeed, must be—if we wish to live full and authentic lives.

Sight is a faculty; seeing, an art.

—George Perkins Marsh

I lost an eye so I might learn to see.

What makes this all the more striking is that I’m a photographer and someone

who savors sight. I love art and the sheer visuality of the world. Herein lies the paradox. I’m highly attuned to visual perception and quite well educated in the physiology, purpose, and pleasure of seeing. And I’m half blind.

Longing for Light is my story, told thirty years after the injury which removed part of my sight. I have decided to give shape to my experiences and discoveries in the form of a memoir essay. The danger of memoir is that it can all to easily slide into narcissistic solipsism that neither benefit the larger needs of the writer or reader. The best writers use their particular experiences to shed light on vaster, more universal aspects of the human condition than their personal lives—as I have tried to do also.

I learned many things about life and vision through losing an eye. I view the

expansion of consciousness that took place through this traumatic experience as a piece,

maybe even a good size chunk, of my legacy that I wish to share. The education of any

one of us can be become an education for all of us, if we view ourselves as an integral

part of the human family.

Longing for Light offers guidance for the general reader on achieving a state

of heightened awareness and developing the gift of observation. The book is intended

for every individual who sees, who questions the nature of seeing, and who wants to

understand more about this mysterious and unexplored capacity. It functions as a catalyst

to stimulate the growth of our perceptual capabilities and has a definite slant toward the relationship between vision and creativity. The gift of observation, of the inner and outer worlds and their profound relationship, can be cultivated—indeed, must be—if we wish to live full and authentic lives.

If we wish to make sense of the world we inhabit, if we wish to assist in meeting

the collective challenges of the modern world, if we wish to be responsible toward

ourselves and each other, and if we wish to attain the great aim of self-knowledge, then

we must develop the courage to see what is, ignoring neither its intrinsic complexity

or its radiant beauty. The voice of conscience often reveals that the world and others

need our deepest attention and care—our real seeing—as well as the actions that arise

genuinely through moments of direct observation.